Paperback: 208 pages

Publisher: Mariner Books; Reprint edition (April 15, 1998)

Sent for you yesterday, and here you come today.

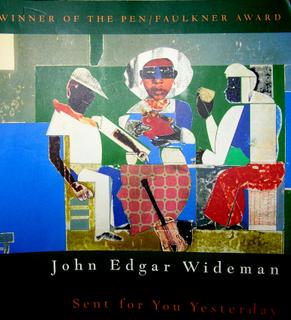

It only makes sense that one of the main themes of John Edgar Wideman’s Pen/Faulkner Award winning novel, Sent For You Yesterday, should find expression in a song. Any novel written with the musical lyricism and jive, stream of consciousness language Wideman employs is attempting to bridge the gap between music and literature. Wideman takes the blues out of the jazz clubs and places it squarely on the page for the readers’ benefit. Sent For You Yesterday is a marvel to read, not only for its eloquent exposition of urban African American culture, but also simply for the beauty of Wideman’s words.

If James Joyce had been born in inner city Pittsburgh instead of Dublin, his writing would most likely have sounded much like Wideman’s. Wideman shifts flawlessly from one characters' thoughts to the next, detailing the exclusion felt by the albino Brother in an all black community, to the lunacy of Samantha, a mother of over 10 children who loses her mind when one of her children burns to death. World War II clouds over this novel in the same way World War I is the ever-present unmentioned in Woolf’s To The Lighthouse. Wideman draws on the modernists, but in a completely original manner. The lives he shows us are real and hard, their importance obviously apparent but unbearably tragic. Through it all, Wideman’s characters persevere, suffering through life, even as they acknowledge it will only get worse. In their brave embrace of life, there is a profound sublimity. One consolation is music – it is also their heritage for people otherwise without possessions.

Any discussion of the characters in Sent For You Yesterday must begin by first acknowledging that the Pittsburgh area of Homewood is the main character. Though he is wanted by the police for sleeping with a white woman, Albert Wilkes’ has to return to Homewood. The place draws him back. He has traveled for seven years but only in Homewood does he feel at home. His re-arrival in Homewood frames the novel’s first section, while the rest of the book focuses on Lucy Tate, the narrator’s Uncle Carl, and Lucy’s surrogate brother called only Brother, and their relative inability to leave Homewood at all. The gravity of the town seems to possess the work’s human characters. Homewood exerts a force originating out of its inescapable history; even as its houses crumble, its people drink and drug themselves to death, and poverty comes to dominate like a despot, Lucy, Carl, and Brother stay fixed, attached to each other, but more so to the place. The only of the self-termed “Three Musketeers” who figures out a way to leave Homewood is Brother and he does so through suicide, symbolically mauled by the town’s lone link to the outside world, a freight train.

Wideman presents his characters not as emblems pleading for our sympathy, but in a matter of fact manner that seems to say: take them as they are or don’t take them at all, either way, your opinion isn’t going to mean much to them. Even as he chronicles the socioeconomic decline from one generation to the next, his characters never turn to external factors to lay blame for their misfortunes. As Carl eloquently recalls about his temporary drug addiction, he enjoyed crack and shot up because of the pleasure. It was his choice, no one else’s. There was no coercion, just as it was his decision to stop. While the oppressive presence of white people hangs over all, penetrating the character’s psyches as if by osmosis, Wideman doesn’t succumb to angry finger pointing. Wideman suggests that the horrendous level of disrespect with which white people treat African Americans has bored into the black mind to such a degree, that the residents of Homewood have internalized and eventually accepted the idea that they are somehow lesser than. It has become so second-hand, the idea isn’t even perceptible anymore. It’s just a part of life, like Carl’s pot belly or the shared affinity for Iron City beer. And it is the subtlety of this presentation of the ramifications of segregation and racism that makes it so effective. How can characters ask for empathy when they can’t even realize they would ever deserve it? The bluesy expression “been down so long don’t even know what’s up,” floats between the lines of Sent For You Yesterday like the lingering echo of a melancholy piano chord.

Wideman justly won the Pen/Faulkner Award for Sent For You Yesterday. His innovative utilization of “authentically black” language provides the dialect and characters with a respect they never afforded themselves. Wideman takes the tuneful acoustics of street slang and transforms the speech into high art. Not since Faulkner has a specific time and place been depicted so accurately and with such heartfelt compassion. Wideman has saved a culture and past from oblivion by rendering it as adeptly as he manages in this novel. In a present when Snoop Dogg and 50 Cent are the most ubiquitous signs of black culture, Wideman reminds all Americans that African Americans have existed and will continue to do so as an incredibly cohesive community and one that we should honor with more than Senate apologies. Wideman illustrates an unshakeable integrity pulsating in a dereliction few of us have or will ever be forced to witness. Whether Homewood’s characters comprehend it or not, they are resilient, and far from pity, should receive only our admiration for not bowing to life’s burdens. As for Wideman, he should continue to receive praise, as an achievement such as Sent For You Yesterday, like the world it defines, must never be forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment