Publisher: Anchor; 1st Anchor Books ed edition (March 16, 1998)

Religious fanaticism reaches an extreme. America’s leaders become more and more conservative in their moral views. The rights of women, minorities, and homosexuals are at first lessened and subsequently removed altogether. An uncontrollable outside enemy, Islamic in its origin, is a threat used to justify the tightened laws and displaced freedoms.

It’s a description that sounds eerily familiar and yet Margaret Atwood wasn’t describing contemporary Bush America, but rather the future state of Gilead, the society in which her Handmaid’s Tale takes place. In the grand tradition of Huxley, Bradbury, and Orwell, Atwood creates a dystopia in which men have completely subjugated women, making the latter mere child-bearing vessels for a culture desperately using religion to at justify its own existence and turn in upon itself. Written in the 1980s, at the peak of Reagan era Christian conservatism, Handmaid’s Tale successfully invokes the image of a society in which a corrupted view of religion becomes the basis for an entire nation of broken up families, government censorship, and legalized rape.

The novel is the first hand account of Offred, a woman forced to be a Handmaid in Gilead. Handmaid’s are birthing machines, with no rights or freedoms, other than the right to have the children of the Commanders, the men who control the society. The Commanders have wives, but these women are long past being able to give birth. So instead, to counteract a dwindling population, decimated by environmental disasters, Handmaid’s are the sole hope for the future. Offred is as much a character as a woman in her position can be. Her role in society is strictly to produce – beyond that she is of no use, and the greater the anonymity of her persona, the smoother her life will be. There is no way to fight those in charge. Any protest leads to death or deportation to a distant wasteland and a lifetime of disposing of nuclear spillage.

But though the leaders of Gilead try to indoctrinate her, Offred cannot forget her past life – her husband Luke, her hippy mother, her daughter. It is these memories she clings onto as the single motivating force keeping her from suicide. Even as her resistance wilts and she foresees the future generations in which any type of different life will have been forgotten, Offred tries to remain some vestige of her old self. Though dystopian novels usually suffer from underdeveloped characters, Atwood masterfully makes Offred a complete person, one which the reader comes to care about, only furthering the affect of her disturbing story.

Atwood’s ability is only rivaled by her achievement. The Handmaid’s Tale, perhaps more so than any other novel of its kind, illuminates the way culture and morality are entirely relativistic concepts. While President Bush may wage war between his good and evil duality, reality, as Atwood shows us, is far more complicated. The Commanders argue Gilead allows women to live better than before, as the fairer sex no longer has to worry about being sexually objectified, exploited in pornography, or raped against their will. The irony of the situation is obvious to the reader. When rape becomes a government endorsed program, women no longer have the capability to exert a will for the act to be against. When criminality becomes legality, to what authority can the oppressed appeal? Morality and religion are tools of the government used to serve their own ends. But even as the reader realizes this, he is required to ask himself about his own society and the very things Gilead rails against. Contemporary society treats women as objects, just in a different way from the members of Gilead. It is up to the reader to decide which state is more desirable. Atwood craftily leaves her tale ambiguous and open-ended, many more questions posed than answered.

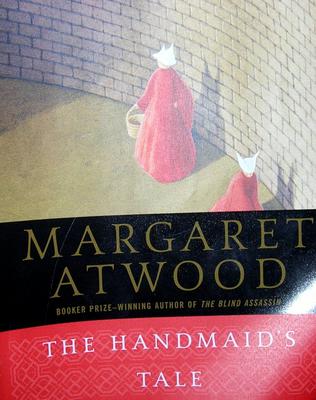

Language, all its possibilities, all its power of persuasion and domination, ripples through Atwood’s pages like a motor boat’s wake. As in other dystopias, most memorably Orwell’s 1984, language is both a tool of repression and a possible means for reaching the salvation of freedom. Atwood plays constantly with her words. The signal to the reader comes immediately in Offred’s name, signifying both her position in society as being “of – Fred” or Fred’s (the Commander’s) Handmaid and yet simultaneously indicating Offred’s hatred of and tenuous position within the society. All Handmaid’s are required to wear red dresses (along with confining white headgear), and thus Offred’s name can be seen as an emblem of the way she is internally removed from the future America in which she is forced to suffer. Her soul is certainly off red in color.

Atwood writes in a terse style, though Biblical allusions abound in her prose. Hers is an accessible, yet deeply complicated and layered narrative, fitted with just enough ironic black humor to keep the reader from complete depression. One does not have the sense Atwood is a writer consumed by hatred of her subject, though her objection to the material is clear. But she lays out the possible dilemmas and problems of conservative Christianity taken to its extremes with a level and measured tone. In a contemporary America is which “Culture Wars” wage and close-mindedness and fear of difference is preached by all those in power, The Handmaid’s Tale still resonates long after the Reagan era of its publication. Atwood’s conceived society is pertinent today not only as a reminder of how power corrupts and morality is flexible, but also as an aesthetic powerhouse seldom equaled in literature of any kind.

No comments:

Post a Comment